Marilyn Krukowski, professor emerita in the department of biology, passed away Sunday, April 7, in St. Louis from complications of multiple sclerosis. She was 80. A more complete obituary will follow.

Obituary: Marilyn Krukowski, age 80

In the Next Room (or the vibrator play)

Sophomore Kiki Milner as Mrs. Catherine Givings. Photo by Rob Morgan. Download hires image.

On this noble roster of pioneering electrical inventions belongs a plain wooden box, decorated with a few twisting knobs and attached to a bulbous device that, to modern eyes, vaguely suggests a hair dryer or a hand-held mixer.

“It looks like a farming instrument,” observes Mrs. Catherine Givings, wife of the Victorian gynecologist Dr. Givings.

But this is no farming instrument. This is science. This is medicine.

This is Sarah Ruhl’sIn the Next Room (or the vibrator play), one of the most criticallyacclaimed comedies of recent years.

This month, Washington University in St. Louis’ Performing Arts Department in Arts & Sciences will present an all-new staging of Ruhl’s Pulitzer- and Tony-nominated work as its spring Mainstage production. Performances run April 19-28 in Edison Theatre.

“In the Next Room is a perfect university play,” says director Henry Schvey, professor of drama. “It interweaves thoughts and ideas from across the arts and sciences. It’s as much about psychology, medicine and the history of technology as it is gender studies.

“And of course, it’s also very, very funny.”

The cast of In the Next Room. Photo by Rob Morgan. Download hires image.

Set in upstate New York in the 1880s, In the Next Room opens with Catherine tending to her infant daughter, Letitia, while Dr. Givings prepares to meet a new patient.

Mrs. Daldry is frail and nervous and painfully sensitive to light and cold — afflictions that render her incapable of playing the piano or otherwise entertaining her husband.

“You have no idea what a source of anguish my wife’s illness has been to me,” complains Mr. Daldry. “And to her, of course.”

Givings diagnoses hysteria, likely due to a congestion of the womb. And so, with a hat-tip to Thomas Edison — “that great American” — the benevolent doctor prescribes a new electrical instrument capable of inducing paroxysms of release. “We shall be done in a matter of minutes,” he assures the nervous woman.

“Givings is an enthusiast, a man of science,” Schvey explains. “From a contemporary perspective, a diagnosis of hysteria is pure poppycock. But we don’t have the sense that he’s subliminally acting out his own desires. He’s basically an innocent. Women were not supposed to be sexual creatures.”

Schvey notes that the walls between the doctor’s office and his living room, where Catherine chats amiably with Mr. Daldry, make a neat allegory for the period’s gender divide.

“Dr. and Mrs. Givings are a couple of their time,” Schvey says. “They treat one another with a tremendous amount of formality, and Mrs. Givings knows nothing about what's going on in the next room. But she has all this suppressed energy, and she becomes increasingly curious — and concerned.

“I think Ruhl raises very serious questions about technology,” Schvey adds. “Electricity is the means to a kind of liberation, but there’s also an implication that something is lost — an idea that I think has real resonance in an era of computers and cellphones.”

Still, at root, Schvey sees a love story.

“It’s like a Shakespearean comedy,” he concludes. “The vibrator becomes like the magical flower in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It causes people to fall in love, and dissolves the walls between the sexes.

“In the end, it's a celebration.”

Senior Gaby Schneider as the midwife Annie. Photo by Rob Morgan. Download hires image.

Leading the cast of seven are senior Pete Winfrey and sophomore Kiki Milner as Dr. and Mrs. Givings.

Senior Gaby Schneider is the midwife Annie. Senior Phoebe Richards is Mrs. Daldry, with St. Louis actor Jack Dryden as her husband.

Freshman Dana Robertson is Elizabeth, Letitia’s wet-nurse. Ricki Pettinato is Leo, an artist hoping to revive his flagging creativity.

Scenic and costume design are by Rob Morgan, senior lecturer in drama, and Bonnie Kruger, professor of the practice in drama. Design and technical coordinator Sean Savoie is in charge of lighting. Props are by Emily Frie, and junior Simeng Zhu handles sound design.

Senior Melissa Freilich is assistant director. Freshman Alexander Booth is stage manager.

Medical exhibition

In conjunction with the play, the Becker Medical Library at the WUSTL School of Medicine will present "In the Next Room: Medical Treatment of Women with 'Hysteria.'" The exhibit examines the various ways this peculiar disorder was viewed in both a medical and a social context from the 16th to the late 19th centuries.

Included are five antique vibrators, dating from the early 1900s to the 1920s, on loan from the Center for Sex and Culture in San Francisco.

Tickets

Performances of In the Next Room (or the vibrator play) will take place in Edison Theatre at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, April 19 and 20; and at 2 p.m. Sunday, April 22. Performances will continue the following weekend, at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, April 26 and 27; and at 2 p.m. Sunday, April 28.

Edison Theatre is located in the Mallinckrodt Center, 6445 Forsyth Blvd. Tickets are $15, or $10 for students, seniors and WUSTL faculty and staff. Tickets are available through the Edison Theatre Box Office, (314) 935-6543, and through all MetroTix outlets.

For more information, call (314) 935-6543 or visit padarts.wustl.edu.

Music and friendship with the Eliot Trio

The Eliot Trio will perform works by Mozart, Brahms and Wieck-Schumann at 8 p.m. Friday, April 12. From left to right: Seth Carlin, professor of music; David Halen, concertmaster for the St. Louis Symphony, and Bjorn Ranheim, also with the St. Louis Symphony.

Even after marriage—in 1837, to her tutor, Robert Schumann—Clara enjoyed great success as a concert pianist, performing works by her husband and other Romantic composer while also raising the couple’s eight children.

Portrait of Clara Wieck-Schumann (1840) by Johann Heinrich Schramm.

The program will open with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Trio (Sonata) in G major. Completed in 1786, the piece is second among the composer’s six piano trios, and the longest. It was likely written for Franziska von Jacquin, one of Mozart’s most talented students, and the daughter of his friend Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin.

Next will be Wieck-Schumann’s Piano Trio. Written in 1846, when the composer was pregnant with her fourth child (and thus unable to tour), the Piano Trio is among Wieck-Schumann’s most fully realized works. Divided into four movements—Allegro moderato, Scherzo: Tempo di Menuetto, Andante and Allegretto—the piece is notable for its lyrical expression, flowing melody and deft use of counterpoint.

Concluding the program will be Trio opus 8 in B major by Johannes Brahms. A close friend to both Shumanns, Brahms began the Trio in early 1854 and completed it shortly after spending a week in their company.

But in 1889, Brahms elected to revisit the work, announcing in a letter to Clara that, “I have rewritten my B major Trio.... It will not be as wild as before - but will it be better?" It is this version that the April 12 program will feature.

Eliot Trio

Tickets are $25, or $15 for seniors and Washington University faculty and staff, and $5 for students. The performance will take place in Holmes Lounge, located in Ridgley Hall, on the far side of Brookings Quadrangle, near the intersection of Hoyt and Brookings drives.

Tickets are available through the Edison Theater Box Office, (314) 935-6543, and all Metrotix outlets. For more information, call (314) 935-5566 or email daniels@wustl.edu.

Media Advisory: St. Louis Walk of Fame induction ceremony for Gerald Early today

WHAT: A ceremony marking Early’s induction into the St. Louis Walk of Fame

WHERE: In front of the Moonrise Hotel, 6177 Delmar Blvd.

WHEN: 11:30 a.m. Thursday, April 11

WHY: Gerald L. Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters at Washington University in St. Louis, will join other WUSTL literary luminaries on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

A native of Philadelphia, Early has been on the WUSTL faculty since 1982.

He is a professor of English, of African and African-American studies, and of American culture studies, all in Arts & Sciences. He recently stepped down as director of Arts & Sciences’ Center for the Humanities after more than 11 years in that position.

A prolific writer, Early is author and editor of more than a dozen books and winner of prestigious literary prizes.

“It’s amazing to me the number of literary greats on the walk who have connections to Washington University, from such faculty members as William Gass, Howard Nemerov and Stanley Elkin to alumni A. E. Hotchner and Tennessee Williams,” said Edwards. “Gerald Early is most deserving of his place alongside these acclaimed writers.”

NOTE: Early’s star, which will be at the ceremony, will be embedded at a later time near the corner of Delmar and Eastgate Avenue after construction is completed on the first phase of Washington University’s Loop Student Living Initiative.

The St. Louis Walk of Fame consists of more than 130 sets of brass stars and bronze plaques honoring individuals from the St. Louis area who made major national contributions to America’s cultural heritage.

For more on Early and the induction ceremony, visit here.

Next Generation Science Standards released

The Next Generation Science Standards have been released, and Washington University in St. Louis members are playing significant roles.

Michael Wysession, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Arts & Sciences, was among the 41-member team that helped write the standards. And WUSTL's Institute for School Partnership (ISP) is poised to help K-12 schools implement them in the St. Louis region.

"This is revolutionary in many respects," Wysession said. "First of all, it is incredible to have most states in the country adopting a single standard. Having each state do its own thing has been really detrimental to the science and engineering education of this country and this is a tremendous step forward.

"The move away from learning long lists of facts and toward assessing students on what they can do and not what they know is incredibly important in training the workforce for tomorrow and in giving all Americans a greater appreciation of science," Wysession said. "The greater emphasis on societally relevant topics, in particular the high emphasis on earth science and climate, is a very important step forward in making science exciting and relevant to people’s lives."

“It’s a whole new vision of what it means to be scientifically literate,” said Victoria L. May, assistant dean of Arts & Sciences and executive director of the ISP. “We’re moving from standards that were very fact-based — telling students ‘here’s all the information you need to know’ — to a much more conceptual approach because of the information age."

Twenty-six states and their broad-based teams worked together for two years with a 41-member writing team and partners to develop the standards, which identify science and engineering practices and content that all K-12 students should master to be fully prepared for college, careers and citizenship.

"The standards really are much more focused on 'what does it mean to do science and the process of engineering," May said. "It’s how to ask the questions, how to pose the problems, how to think things through. That’s what the ISP has been about all along.”

“Kids learn science by doing science — not just reading about it in a textbook and then looking at vocabulary terms,” May said. “We provide materials and supplies that enable students to explore concepts and make sense of them.”

And now that the new standards are in place, the services the ISP provides to the St. Louis region are going to be more important than ever.

“It’s going to be much easier to collaborate with common standards,” May said. “With every state having its own testing system, you really weren’t able to compare and learn from the data. This is going to make it much easier to leverage each work between states.”

To learn more about Wysession's involvement in the process, read here.

To learn more about the ISP, visit www.schoolpartnership.com.

Moore installed as John and Penelope Biggs Distinguished Professor of Classics

Mary butkus

Penelope and John Biggs visit with Timothy J. Moore, PhD, right, at a ceremony celebrating Moore's installation as the inaugural John and Penelope Biggs Distinguished Professor of Classics in Arts & Sciences.

The professorship was established in 2002 with generous gifts from distinguished Washington University alumni John and Penelope Biggs. The Biggses were among the special guests who attended the ceremony last November where Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton presented Moore with a university medallion to celebrate the occasion.

“Our students and the Washington University community will benefit tremendously from John and Penelope’s steadfast support of the classics. I am extraordinarily grateful to them for establishing this distinguished professorship,” Wrighton said. “Endowed professorships constitute a direct investment in academic excellence as exemplified by the inaugural holder of the Biggs Distinguished Professorship, Professor Timothy J. Moore.”

Moore joined Washington University in July 2012 from the University of Texas at Austin, where he had served as a professor of classics since 1991 and chair of the Department of Classics from 2002-04. From 1986-1991, he was an assistant professor at Texas A&M University and then spent a year as a Mellon Faculty Fellow at Harvard University.

He earned a doctoral degree in classics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1986 and a bachelor’s degree in Latin and history, summa cum laude, from Millersville University in 1981.

Moore’s work focuses on classical antiquity, including the comic theater of Greece and Rome, Greek and Roman music and Roman historiography.

His current projects include articles on the music in two plays of the Roman comic playwright Terence and a long-range project on the influence on the modern world of the Roman historian Livy. His interests also include the history of theater, especially American musical theater and Japanese Kyogen comedy. In the fall, he plans to teach a course on ancient Greek and Roman music – a first for WUSTL.

Moore’s speech at the installation ceremony, “Building Bridges in Classical Studies,” touched on a theme dear to him: bringing together different skills and academic disciplines to study classics.

One of Moore’s goals is to create a doctoral degree in classics, working with other departments like history, performing arts and philosophy, for example.

Moore said it’s important to study classic Greek and Roman culture because they have a strong influence on the modern world, in everything from the calendar we use to the design of buildings.

“Studying ancient Greeks and Romans is in some ways like studying ourselves,” he said. But at the same time, he said, such study also allows for an appreciation of diversity because elements of that world were much different from our own.

Cambridge University Press published his most recent book, Music in Roman Comedy, in 2012. Moore’s other books are Roman Theatre (also from Cambridge University Press, 2012); The Theater of Plautus: Playing to the Audience (University of Texas Press, 1998); and Artistry and Ideology: Livy’s Vocabulary of Virtue (Athenäum Press, 1989).

He also has written numerous articles and book chapters and received various awards, including a DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) Fellowship in 2011, a Rome Prize Fellowship at the American Academy in Rome and a Loeb Classical Library Foundation Fellowship.

Moore, who has organized various scholarly events, most recently served as co-director of the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute for College Teachers: “Roman Comedy in Performance” in 2012.

George Pepe, PhD, former department chair and also a professor of classics, said Moore brings the right skills and is a welcome addition.

“We were extremely fortunate to lure Tim away from University of Texas. He’s a very distinguished scholar in Latin literature and a first-rate teacher,” Pepe said. “He brings with him the right blend of scholarship and administrative experience to lead the department successfully.”

About John and Penelope Biggs

Both John and Penelope Biggs are longtime friends of the university, alumni of Arts & Sciences with a dedication to keeping the classics alive.

For more than 20 years, WUSTL has benefited from a residency in the classics department created by the Biggses, whereby a prominent scholar in Greek or Latin studies visits the university for a week to teach and promote an area of the classics. In 2002, the couple made a commitment to establish the John and Penelope Biggs Distinguished Professorship in Classics. They also have established a distinguished professorship in economics.

Native St. Louisan John Biggs is an eminent economist with a lifelong interest in advancing education. He earned a bachelor’s degree in classics from Harvard, and his first job was with General American Life Insurance Co., where he ascended through the ranks. He also served as vice chancellor for finance and administration at WUSTL from 1977-1985, when he became president and chief executive officer of Centerre Trust Inc.

During his tenure at Washington University, he earned a doctorate in economics and taught classes in the department.

He later served as chief executive officer of investment company TIAA-CREF, and led the company until retiring in 2002.

Since his retirement, Biggs has remained active in corporate, community and professional associations.

Penelope Biggs graduated summa cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in classics from Radcliffe College, where she first met John while he was a student at Harvard.

She earned a master’s degree and a doctorate in comparative literature from Washington University in 1968 and 1974, respectively. She joined the faculty of Lindenwood College (now University) as an assistant professor of literature.

Later, she taught Latin at the high school now known as Mary Institute Country Day School. Her writings on classical and post-classical literature have been published in scholarly journals.

John and Penelope Biggs are members of Washington University’s Danforth Circle Chancellor’s Level and life members of the Danforth Circle Dean’s Level. Together, they received the Robert S. Brookings Award in 2009.

John Biggs is an emeritus trustee of the university and received the Arts & Sciences Dean’s Medal in 2005. He also received an honorary doctor of humane letters degree in 2011 and a New York Regional Award in 2006 for outstanding professional achievements and service to Washington University. John currently serves on the Arts & Sciences National Council, as a volunteer for Leading Together: The Campaign for Washington University, and as an honorary member of the New York City Regional Cabinet.

Prestigious recognition from French government

KeVin Lowder

Alumna Anna DiPalma Amelung, PhD, a facilitator at the Lifelong Learning Institute (LLI) at Washington University in St. Louis, was inducted as a Chevalier dans L'Ordre des Palmes Académiques (Knight in the Order of Academic Palms) for outstanding contributions to the development of French culture and language. Jean-Francois Rochard, the attache cultural adjoint consulate general of France in Chicago, presented Amelung with a medallion on behalf of the French government during a March 22 ceremony and reception at the West Campus Conference Center. Amelung, who has facilitated 16 courses at the Lifelong Learning Institute over the past three years, gave a lecture titled "In Praise of Franco-American Friendship: Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas" during the event. Amelung earned a PhD in French from WUSTL. The Ordre des Palmes Académiques is the oldest non-military decoration in France, founded by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1808 to honor educators. LLI is a community outreach education program sponsored by University College in Arts & Sciences that offers a variety of non-credit academic courses for senior adults. A teacher for 45 years in Europe and the United States, Amelung refers to LLI students as "the most exciting and rewarding student body one can only dream of."

Gerald Early's St. Louis Walk of Fame induction ceremony talk

Gerald L. Early, PhD, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters at Washington University in St. Louis, delivered the following address during his induction ceremony into the St. Louis Walk of Fame April 11 on Delmar Boulevard in The Loop.

Also speaking during the ceremony was Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton and Joe Edwards, founder of the St. Louis Walk of Fame and owner of numerous Loop businesses, including Blueberry Hill and the Moonrise Hotel, where the ceremony took place.

St. Louis Walk of Fame induction ceremony talk by Gerald Early

It is difficult to give an appropriate response to receiving an honor like this. To say that you don’t deserve it assails the judgment of the people who chose you for it. To say that you deserve it is an admission that you don’t know how to judge yourself objectively. So, as with any gift, it is best simply to accept it with gratitude.

I wish to thank Joe Edwards for establishing the Walk of Fame and for his kindness. Of course, I thank all the people who voted for me to have this plaque. It would not have been possible for me to have won this award without the support of Washington University, which has been so central to my career. I am indebted to the leadership there, Chancellors Danforth and Wrighton and to the various deans of Arts and Sciences who helped me.

I am exceedingly grateful to various colleagues and friends in the English department, in African and African-American Studies, at the Center for the Humanities, and in other departments and schools around the university for what they have done for me. I have the pleasure of working with many fine, very smart, and honorable people. I’ve learned a great deal from my peers.

I regret that the late Jim McLeod is not here today. He was very important to my development during his years as director of the African and African-American Studies Program. He would have been pleased to see me get this sort of recognition. He always believed in my possibilities.

In particular, I wish to thank Bob Archibald, former president of the Missouri History Museum, for permitting me to do two major projects: the Miles Davis exhibit and the Seeking St. Louis writers project, which resulted in two of my most important books, Miles Davis and American Culture and Ain’t But A Place: African American Writings about St. Louis. I am proud of these books and humbled that Bob thought I had the skill to do them.

I owe much to my family, my daughters Rosalind and Linnet, who have grown up to be such mature, responsible adults, my son-in-law, Stan, a good father, husband, and scholar, and my grandsons William and Stanley.

If anyone deserves a plaque like this, it is my wife, Ida, for all her civic work, for her path- breaking leadership of the Junior League, for all the difference that she has made at Washington University, and for her devotion to St. Louis’s nonprofit world. She has always been my model citizen. I wish I had half her zeal and commitment, half her moral clarity and common sense sympathy.

I am so very glad that my mother, my sister, and my cousin are here from Philadelphia for this occasion. My mother, a widow during my childhood and adolescence, provided me with a wonderful childhood and gave me a set of tough, realistic values by which to measure and criticize life. My sister introduced me to books and music. I was the only kid in my neighborhood who had a sister who read to him stories by Charles Dickens and played for him records by Nina Simone, Phil Ochs, Miriam Makeba, and Odetta. And my cousin was with me when I first became a published writer while I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania.

I am pleased as well that my in-laws from Dallas, Texas, are here: My mother-in-law, my sister-in-law, my brother-in-law, and my niece-in-law. They are all such good and generous people who have been so supportive of me over the years. I am honored that they took the time to be here today.

It is clear that many can make a claim to a small piece of this plaque. No one does anything solely through his or her own efforts. No one is his or her own invention. We are rather cobbled together piecemeal by a network of unexpected influences. These influences do not even sort themselves out in the end as good or bad but rather as those we need, those we like, those we think we understand, and those we crave to exorcise but can’t.

I grew up in what today might be called an inner-city neighborhood in South Philadelphia that was made up of African Americans and Italian Americans almost in equal number. The adults were all working class and, no matter their race, they were all conservative people.

Mine was the generation of the Baby Boomers and our parents went through their childhood and teen years during the Depression and World War II. It was those years that formulated their conservative views, their belief in the power of the Christian church, in the necessity of school, the sanctity of marriage, the shame of teen pregnancy, the need for a man to earn enough to support a wife and children, the need for a woman to be a good mother and housewife and to keep an eye on the neighborhood during the day, the wonders of home ownership.

They believed that too much egalitarianism was a form of decadence, and harbored great suspicions of a new trend afoot called credit cards. I was taught it was horrible to borrow money but lots of adults then were buying on the “e-z” installment plan and borrowing from credit unions. Nearly everyone smoked including many of us kids. Everyone was on the lookout for a buck and a little luck, so everyone, black and white, played the illegal lottery. And nearly everyone, black and white, went to the nearby Catholic elementary school every week to play bingo.

Several of the black women in the neighborhood cleaned the homes of some of the white women; and many black teens worked in the small shops owned by the Italians and the Jews. Many of the blacks in the neighborhood lived in housing projects; none of the whites did. There was an overt racial hierarchy and we had our share of racial conflict. But surprisingly people got on with one another reasonably well.

Everyone in the neighborhood believed in unions and voted for Democratic Party every election because everyone could count on Democrat politicians like Rep. Bill Barrett to do favors for you like getting your kid out of jail without paying bail if he had been arrested on a misdemeanor or getting your driver’s license back after it had been suspended for drunk driving, or helping your kid get out of the army without being dishonorably discharged or helping your kid get into the police academy or something like that.

Our politics was the ideology of patronage. This working class conservatism had severe shortcomings as it was partly built on intolerance, superstition, political corruption, and prideful ignorance but there was much about this community’s conservatism that made my childhood stable and warm and rich in the gifts of ordinary life, even if it was narrow in its exposure and unenlightened about the wider world. I am what this neighborhood made me.

A few years ago I took my daughter Rosalind on a walking tour of this neighborhood. She was surprised by how modest it was, despite a few touches of gentrification. She was even more surprised when we ran into people, black and white, who knew me, had grown up with me, and remembered me despite the fact that I had not lived there for over 35 years and had not seen these people in years.

She was surprised as well that I was held in such esteem by them. “I was lucky. The people in this neighborhood always believed in my possibilities,” I said to her.

When we arrived at an old ball field, I told her a story of how I used to play baseball for my elementary school team, how bad I was as a player then, and how the kids and the gym teacher made me a catcher, a position nobody wanted to play. I was afraid of the ball, afraid of being hit by the bat when I was catching, afraid of striking out when I was batting, which I always did. The opposition called me the automatic out, the clown, hole in the glove, and the weakling.

One day I was really struggling, making errors and striking out, and I was getting razed by both the opposing team and my own teammates who yelled at me “Why the hell can’t you hit anything?” So, finally, I simply sat down on the bench, started to cry, and refused to play anymore. I was tired of being humiliated.

The gym teacher was furious with me and told me I wouldn’t amount to much of a man if I couldn’t take adversity, if I couldn’t take some hazing. Look at what Jackie Robinson had to take, he said. That odd appeal to racial pride might have worked but I was only 10 years old and was convinced in my child’s mind that Jackie Robinson could not have suffered nearly as much as I had.

The opposition really gave it to me and called me a sissy, a crybaby, and the like. But my teammates did not raze me or even get mad, they came over and earnestly talked me back into playing. They told me not to let them down and we had to stick together as a team. As bad as I was, they still wanted me.

My best friend, Benny, handed me the catcher’s mask and mitt and said, “God hates a coward.” He grew up to become a preacher and was always a devout kid. So I went back into the game. In the last inning of that game, we were ahead by one run. The opposition had a runner on first with two outs and the batter hits a ball into the gap. The kid on first was tearing around the bases. Amazingly, we made absolutely perfect relays and I got the ball just as this husky kid came barreling toward the plate and he ran right over me, flattened me completely. I actually saw stars. That’s how hard he hit me.

Rosalind thought the story had a sad ending. She thought the opposition won.

Oh no, I told her. The kid was out. I tagged him and held on to the ball. It didn’t matter that he knocked me into the middle of next week. We won the game and I was a hero.

I told her that I learned everything from that game. First, I learned that while I wasn’t as good as I wanted to be, I wasn’t as bad as I thought I was. And that I didn’t need to be better than everyone else. I only needed to be the best at the crucial moment when it counted most.

Second, the only way to stop being embarrassed and humiliated was to get better. There is a certain kernel of cruelty in all learning. Third, from time to time, you need someone who believes in your possibilities to tell you to trust your stuff, as they say in baseball, because God does indeed hate a coward.

Rosalind thought it was a good story. She understood the neighborhood was more than she thought it was, it had more to offer than was apparent on its surface.

I also learned one other thing, I told her. Long before Tom Hanks said it in a movie, I learned that there is no crying in baseball.

Gerald Early gets star on St. Louis Walk of Fame

Washington University Professor Gerald L. Early, PhD, an internationally renowned essayist and American culture critic, was recognized with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame during an April 11 induction ceremony in front of the Moonrise Hotel on Delmar Boulevard in The Loop.

The St. Louis Walk of Fame consists of more than 130 sets of brass stars and bronze plaques honoring individuals from the St. Louis area who have made major national contributions to America’s cultural heritage.

Joe Edwards, founder of the St. Louis Walk of Fame and owner of numerous Loop businesses, including the Moonrise and Blueberry Hill, noted that Early was joining other WUSTL literary luminaries on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

“It’s nothing short of phenomenal how many people in the St. Louis Walk of Fame have some connection to Washington University,” he said. “Either they attended, they taught or have done research there.”

All Photos by Whitney Curtis

Gerald L. Early, PhD (left), receives a plaque from Joe Edwards marking Early’s induction into the St. Louis Walk of Fame during an April 11 ceremony in front of the Moonrise Hotel on Delmar Boulevard in The Loop.

In his induction speech, Early talked about lessons he learned while growing up in a tight, working-class neighborhood in South Philadelphia. Among the people he thanked was his mother, who was in the audience. “My mother, a widow during my childhood and adolescence, provided me with a wonderful childhood and gave me a set of tough, realistic values by which to measure and criticize life.” To read his talk from the ceremony, visit here.

Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton, who spoke during the ceremony, congratulates Early. In his remarks, Wrighton said that he normally does not celebrate failure, but noted one time early in his career that he was thankful for not succeeding. That was when Wrighton was provost at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and he tried wooing Early from WUSTL to MIT.

Colleagues, friends and family — including his mother, sister and cousin from Philadelphia and in-laws from Dallas — attended Gerald Early's St. Louis Walk of Fame induction ceremony. Early, a professor of English, of African and African-American studies, and of American culture studies, all in Arts & Sciences, recently stepped down as director of the Center for the Humanities after more than 11 years in that position. The center and African and African-American studies hosted a reception for Early later in the day in the Women's Building Lounge.

Jacoby wins Lifetime Achievement Award for contributions to experimental psychology

The Society of Experimental Psychologists (SEP) has awarded its 2013 Norman Anderson Lifetime Achievement Award to Larry L. Jacoby, PhD, an internationally recognized scholar of human memory and a professor of psychology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Jacoby

Founded in 1904, the society is an honorary elected group of about 200 psychologists. The Norman Anderson Lifetime Achievement Award is given to senior individuals with outstanding records of sustained contribution to experimental psychology.

“Dr. Jacoby is hugely deserving of receiving this honor,” said SEP secretary-treasurer Robert Nosofsky. “For decades, he has made extraordinarily creative, insightful and significant contributions to the study of memory and to the distinction between consciously controlled and automatic cognitive processes.

“Among his numerous major contributions involves his insight that individual cognitive tasks do not provide pure measures of single processes. Through ingenious experimental and modeling techniques, Jacoby has enormously advanced our ability to measure the joint roles of consciously controlled and automatic processes in varieties of task performance. The applications of his ideas are extremely far reaching, allowing researchers to better understand age-related differences in memory, fundamental issues in the domain of social psychology, and a variety of intriguing memory illusions.”

Jacoby earned his doctoral degree in psychology from Southern Illinois University Carbondale in 1970 and took his first faculty job at Iowa State University. In 1975, he moved to McMaster University in Canada, where he would remain for much of the next 25 years. He joined Washington University as a professor of psychology in Arts & Sciences in 2000.

In a career spanning four decades, he has made numerous influential contributions to both cognitive and social psychology, especially in the areas of human memory and cognitive aging.

In the 1970s, Jacoby worked on topics of transfer of information from short-term to long-term memory and on the levels of processing approach to memory. Both these topics were at the cutting edge of research in the 1970s, and he made significant contributions to them. In the 1980s, he turned his attention to an emerging field that came to be called implicit or indirect measures of memory.

One of the main starting points of this revolution in the study of memory came from a 1981 paper that Jacoby co-published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, which showed, for the first time, that variables that have huge effects on standard explicit measures of memory such as recognition have either no effect or an opposite effect on implicit measures of memory – in this case, a word identification test.

Jacoby and colleagues published many other impressive investigations on this topic, including pioneering studies of “memory attributions” that examined the influences of implicit forms of memory and how they could occasionally intrude into conscious decisions, and vice versa. For example, his work on the false fame effect or “becoming famous overnight” showed that when people are exposed repeatedly to a nonfamous name, such as Sebastian Weisdorf, and then time passes so that they no longer explicitly recollect having seen the name, they would later judge the name as being famous.

In 1991, Jacoby made one of his most important contributions when he published a paper on the ingenious process dissociation procedure, which permits separate estimates of the contributions of controlled and automatic processes in a variety of tasks, and has had a huge influence on research in several fields of psychology. The paper has been cited more than 2,500 times.

Around this time, Jacoby also initiated his studies of cognitive aging, which during the past two decades have used a number of novel techniques he developed to illuminate the interplay between conscious and nonconscious memory processes in older adults, including demonstrating that older adults are particularly susceptible to false fame effects as well as other memory errors and illusions.

At Washington University, Jacoby directs the Aging, Memory and Cognitive Control Lab in the Department of Psychology. Research in the lab focuses on questions related to cognitive control and to subjective experience, especially the distinction between consciously controlled and automatic processes. Other research investigates age-related differences in memory and perception, memory illusions and cognitive factors influencing learning and education.

Summer Writers Institute now even more convenient for working professionals

The changes were made because participants asked for a “little more breathing room” in the schedule, said Pat Matthews, associate dean of University College in Arts & Sciences and director of Summer School.

Evening sessions this year will meet Monday, Wednesday and Friday instead of Monday through Friday. Also, the weekend sessions will be afternoons only instead of daylong seminars. The institute begins July 12 and runs through July 26.

“I had not been able to participate in the institute until last year, when the evening and weekend format better fit my schedule,” said Colleen Corbett, programs manager in Student Technology Services. “What is especially valuable about the institute is that by the end of the program, most of us writers had at least one polished piece that held high potential for publication.”

Corbett took the creative nonfiction workshop last year, which is offered again this year along with poetry, fiction and flash fiction.

“I had a wonderful experience and have recommended the institute to friends and colleagues,” said Nancy Berg, PhD, professor of modern Hebrew language and literature and of comparative literature, both in Arts & Sciences. “I continue to benefit from the workshop in both my writing and teaching.”

The focused format sparks an intense creative experience for the participants.

“One thing I like about this condensed two-week format is the pressure it applies to the experience,” said David Schuman, one of the institute’s instructors. “Pressure isn’t always considered such a great motivator, but in this case you’ve got a group of people, all hungry for experience, with a feast in front of them — readings, lectures, panels and workshops. There’s a sense of urgency that often influences rapid growth. I’ve seen students take leaps I wouldn’t have expected. Synapses are rapid-firing, pens are flying, words are filling the air. Everything a growing writer needs.

“What excites me about the institute is the close-knit group of writers that blooms during the short span of the session,” said Schuman, a lecturer in the Department of English, in Arts & Sciences. “It’s almost like watching a photograph develop — things are fuzzy at first, you’re interested in what’s going to happen, and then at the end an image has crystallized.”

The four genres:

Fiction, taught by Colin Bassett, lecturer in the Department of English. This workshop discusses the writing process and ways to make a story detailed and vivid while also keeping it moving forward. Close attention will be paid to the rhythm and texture of language. Bassett’s story "This Is So We Don't Start Fighting" was listed as a distinguished story in The Best American Short Stories. His writing has been awarded the Carrie S. Galt Prize in Fiction and received an honorable mention from the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Intro Journals Project.

Flash Fiction, taught by Schuman. Borrowing strategies from the novel, short stories, prose poems, haiku and other short forms (fables, folktales, pop songs), students boil stories down to their essence. Schuman won a Pushcart Prize in 2007, and his story "Stay" was listed as one of 100 distinguished stories in The Best American Short Stories.

Creative Nonfiction: Personal Narrative, taught by Kathleen Finneran, writer in residence in the Department of English and author of the memoir The Tender Land: A Family Love Story. This workshop focuses on creating works of literature using personal life as subject matter. Finneran is the recipient of a Whiting Writers Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Poetry, taught by Kent Shaw, assistant professor of English at West Virginia State University. Writers will focus on each other’s poetry to refine the voice and imagery. Shaw’s first book, Calenture, was published in 2008. His poems have appeared in The Believer, Boston Review and many other publications.

All courses are offered through University College. Tuition is $1,830. Each workshop is worth 3 units; no application is required.

For more information and to register, visit here.

Encouraging literacy: Education students donate more than 350 books to local grade school

For the fifth year in a row, the Washington University in St. Louis members of Kappa Delta Pi (KDP), the international honor society in education, led a service project that focuses on literacy and benefits local grade-schoolers.

Pre-K through sixth-grade students and their teachers at Cool Valley Elementary School in the Ferguson-Florissant School District were the lucky recipients of more than 350 books donated by KDP members.

The eleven KDP members, both undergraduate and graduate students in WUSTL’s Department of Education in Arts & Sciences, held fundraisers and wrote successful grants to the Women’s Society of Washington University and the education department to help pay for the books, which they delivered to the school April 12.

Each Cool Valley student received a book, which they selected in advance, along with a personalized bookmark. Each of the school’s 18 teachers received a basket of five books for their classrooms.

“This project is such a wonderful opportunity to boost literacy in the homes of our students,” said Suzette Simms, Cool Valley principal. “For the Washington University students to choose our school for this service project and to choose books that our students are interested in reading is awesome.”

all photos by Sid Hastings

Allison Laird, an Arts & Sciences junior majoring in education and president of KDP, reads “Leah's Pony” to third-graders at Cool Valley Elementary. In addition to delivering books to the school, the WUSTL education students also delivered a lesson as part of their service project, titled “On the Move: Encouraging Literacy.”

Eileen Lai, a senior majoring in education, watches as kindergartners balance bean bags on their heads as part of Lai’s lesson on the timeless classic “Caps for Sale” about a cap salesman who wears his entire stock of caps on his head.

Laird receives appreciative hugs from third-graders at Cool Valley Elementary School after she and her fellow KDP honor society members hand-delivered books to the students. WUSTL's KDP chapter members have purchased and donated close to 2,000 books to area school children in the past five years.

Steinberg wins 2013 Sowden Prize

Steinberg

Lindsey Steinberg has been selected to receive the 2013 Sowden Prize, given each year by the Department of Chemistry in Arts & Sciences.

The prize is named in honor of the late John C. Sowden, a professor of chemistry in Arts & Sciences. A carbohydrate chemist, Sowdon collaborated with the nuclear chemists and radiochemists at Washington University to create radio-labeled carbohydrates that helped to reveal the mechanisms of carbohydrate reactions.

Sowdon was a faculty member at WUSTL for 16 years and chairman of the chemistry department from 1956 to 1963, helping the university earn a reputation as one of the world's leaders in research excellence.

The award memorial fund was established by his family, friends and colleagues after his death in 1963. The Sowden Prize is the highest honor the Chemistry Department bestows on a graduating senior chemistry major.

Richard A. Loomis, Steinberg’s advisor and an associate professor of chemistry, first met her in a physical sciences pre-freshman orientation program. “From day one, she was clearly driven to succeed in a career in science,” he said.

Loomis says that as a sophomore, Steinberg took on a complicated set of experiments to optimize the properties of semiconductor quantum wires. He says she made great strides in less than a year and that her research findings will be part of at least three academic publications.

Steinberg, a Merit Scholar, who is minoring in physics and has a 3.99 GPA, plans to pursue an academic career to “contribute both to innovative research and the education of others.”

Among her extracurricular activities, Steinberg has worked as a Peer-Led Team Learning leader for general chemistry students since her sophmore year. This semester she will receive an Outstanding Peer Leader award.

She has also been a teaching assistant for organic chemistry and for physical chemistry, and a volunteer with Catalysts for Change, a program to introduce female high school students to opportunities available in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields.

Last year she won a $10,000 Astronaut Scholarship Foundation, a foundation established in 1984 by surviving members of America’s original Mercury Seven astronauts to provide scholarships for college students who exhibit motivation, imagination and exceptional performance in the science or engineering field of their major.

The Astronaut Scholarship is the largest monetary award given in the United States to STEM undergraduate college students based solely on merit.

After graduation, Steinberg plans to attend the Washington University Medical Scientist Training Program in pursuit of an MD/PhD..

Grains of sand from ancient supernova found in meteorites

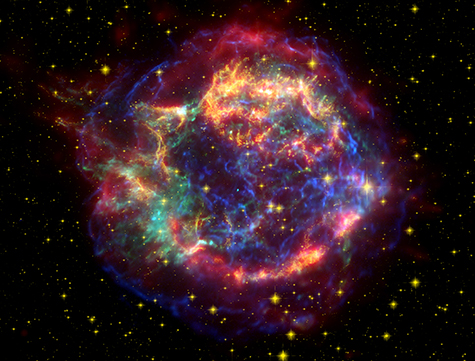

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ O. Krause (Steward Observatory)

In 2007 NASA's Spitzer space telescope found the infrared signature of silica (sand) in the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A. The light from this exploding star first reached Earth in the 1600s. The cyan dot just off center is all that remains of the star that exploded.

It’s a bit like learning the secrets of the family that lived in your house in the 1800s by examining dust particles they left behind in cracks in the floorboards.

By looking at specks of dust carried to earth in meteorites, scientists are able to study stars that winked out of existence long before our solar system formed.

This technique for studying the stars – sometimes called astronomy in the lab — gives scientists information that cannot be obtained by the traditional techniques of astronomy, such as telescope observations or computer modeling.

Now scientists working at Washington University in St. Louis with support from the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, have discovered two tiny grains of silica (SiO2; the most common constituent of sand) in primitive meteorites. This discovery is surprising because silica is not one of the minerals expected to condense in stellar atmospheres — in fact, it has been called ‘a mythical condensate.’

Five silica grains were found earlier, but, because of their isotopic compositions, they are thought to originate from AGB stars, red giants that puff up to enormous sizes at the end of their lives and are stripped of most of their mass by powerful stellar winds.

These two grains are thought to have come instead from a core-collapse supernova, a massive star that exploded at the end of its life.

Because the grains, which were found in meteorites from two different bodies of origin, have spookily similar isotopic compositions, the scientists speculate in the May 1 issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters, that they may have come from a single supernova, perhaps even the one whose explosion is thought to have triggered the formation of the solar system.

A summary of the paper will also appear in the Editors’ Choice compilation in the May 3 issue of Science magazine.

The first presolar grains are discovered

Until the 1960s most scientists believed the early solar system got so hot that presolar material could not have survived.

But in 1987 scientists at the University of Chicago discovered miniscule diamonds in a primitive meteorite (ones that had not been heated and reworked). Since then they’ve found grains of more than ten other minerals in primitive meteorites.

Many of these discoveries were made at Washington University, home to Ernst Zinner, PhD, research professor in Physics at Washington University in St. Louis, who helped develop the instruments and techniques needed to study presolar grains (and the last author on the paper).

illustration Adapted from one by the Nanoscale Informal Science Education Network

How small is small? Presolar silicates typically run 250 nanometers in diameter, which is smaller than a virus but wider than a strand of DNA — and nowhere near visible. For a larger version of this diagram, click here.

The scientists can tell these grains came from ancient stars because they have highly unusual isotopic signatures. (Isotopes are different atoms of the same chemical element that have a slightly different mass.)

Different stars produce different proportions of isotopes. But the material from which our solar system was fashioned was mixed and homogenized before the solar system formed. So all of the planets and the Sun have the pretty much the same isotopic composition, known simply as “solar.”

Meteorites, most of which are pieces of asteroids, have the solar composition as well, but trapped deep within the primitive ones are pure samples of stars. The isotopic compositions of these presolar grains provide clues to the complex nuclear and convective processes operating within stars, which are poorly understood.

Even our nearly Sun is still a mystery to us; much less more exotic stars that are incomprehensibly far away.

Some models of stellar evolution predict that silica could condense in the cooler outer atmospheres of stars but others predict silicon would be completely consumed by the formation of magnesium- or iron-rich silicates, leaving none to form silica.

But in the absence of any evidence, few modelers even bothered to discuss the condensation of silica in stellar atmospheres. “We didn’t know which model was right and which was not, because the models had so many parameters,” said Pierre Haenecour, a graduate student in Earth and Planetary Sciences, who is the first author on the paper.

The first silica grains are discovered

In 2009 Christine Floss, PhD, research professor of physics at Washington University in St. Louis, and Frank Stadermann, PhD, since deceased, found the first silica grain in a meteorite. Their find was followed within the next few years by the discovery of four more grains.

All of these grains were enriched in oxygen-17 relative to solar. “This meant they had probably come from red giant or AGB stars” Floss said.

When Haenecour began his graduate study with Floss, she had him look at a primitive meteorite that had been picked up in Antarctica by a U.S. team. Antarctica is prime meteorite-hunting-territory because the dark rocks show up clearly against the white snow and ice.

MANAVI JADHAV

Haenecour with the NanoSIMS 50 ion microprobe he used to look for presolar grains in a primitive meteorite. The silica grain he found is too small to be seen with the unaided eye, but the microprobe can magnify it 20,000 times, to about the size of a chocolate chip.

Haenecour found 138 presolar grains in the meteorite slice he examined and to his delight one of them was a silica grain, But this one was enriched in oxygen-18, which meant it came from a core-collapse supernova, not a red giant.

He knew that another graduate student in the lab had found a silica grain rich in oxygen-18. Xuchao Zhao, now a scientist at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics in Beijing, China, found his grain in a meteorite picked up in Antarctica by the Chinese Antarctic Research Expedition.

With two specks to go on, Haenecour tackled the difficult problem of calculating how a supernova might have produced silica grains. Before it explodes, a supernova is a giant onion, made up of concentric layers dominated by different elements.

Wikimedia Commons

A massive star that will explode at the end of its life, a core-collapse supernova has a layered structure rather like that of an onion.

Some theoretical models predicted that silica might be produced in massive oxygen-rich layers near the core of the supernova. But if silica grains could condense there, Haenecour and his colleagues thought, they should be enriched in oxygen-16, not oxygen-18.

They found they could reproduce the oxygen-18 enrichment of the two grains by mixing small amounts of material from the oxygen-rich inner zones and the oxygen-18-rich helium/carbon zone with large amounts of material from the hydrogen envelope of the supernova.

In fact, Haenecour said, the mixing needed to produce the composition of the two grains was so similar that the grains might well come from the same supernova. Could it have been the supernova whose explosion is thought to have kick-started the collapse of the molecular cloud out of which the planets of the solar system formed.

How strange to think that two tiny grains of sand could be the humble bearers of such momentous tidings from so long ago and so far away.

Newly established McLeod Writing Prize awarded to first freshmen

The first Dean James E. McLeod Freshman Writing Prize has been awarded, and the inaugural winners are Senit Kidane and Claudia Vaughan.

McLeod was a longtime leader at Washington University in St. Louis, serving as vice chancellor for students and dean of the College of Arts & Sciences, the university’s largest undergraduate program, when he died in 2011 after a two-year battle with cancer.

The Center for the Humanities provided funding for the contest in McLeod’s honor, and any freshman in the College of Arts & Sciences could submit work for consideration. Original research papers exploring an aspect of race, gender or identity and created for a freshman course were eligible.

Kevin Lowder

Clara McLeod, left, widow of Dean McLeod and an earth and planetary sciences librarian, visits with Senit Kidane, a winner of the Dean James E. McLeod Freshman Writing Prize. The Center for the Humanities and the College of Arts & Sciences held a ceremony April 9, during which leaders announced the first winners of the writing prize.

1) “Not Your Ordinary Schoolyard Hustle: Black Women in the Underground Economies of the 1920s,” by Kidane, for her class “African-American Women’s History: Sexuality, Violence and the Love of Hip-Hop.” The paper explores black women’s roles in the aftermath of World War I and their involvement in the complex illegal economies of the time, being active, and sometimes leaders, in prostitution and bootlegging operations, for example. Kidane is majoring in anthropology and in African and African-American studies.

Kevin Lowder

Claudia Vaughan, left, the other winner of this year's McLeod Freshman Writing Prize, shows her certificate to Erin McGlothlin, PhD, interim director of the Center for the Humanities and associate professor of German.

Sowande’ Mustakeem, PhD, assistant professor in history and in the African and African-American Studies program, both in Arts & Sciences, created the writing contest. The center provides prize money and the College of Arts & Sciences offers administrative support, an example of the creative initiatives that are possible when faculty and administrators work in collaboration to support students.

Mustakeem, academic coordinator of the writing prize, said she had planned to approach McLeod about creating a writing contest exclusively for freshmen because in other competitions on campus, their work often was compared to juniors and seniors more versed in the research and writing process. After McLeod died, it became a logical way to honor his life and his concern for students and the value of an education, she said.

“It’s helping to extend Dean McLeod’s legacy,” she said. “This is an opportunity for freshmen to see themselves as scholars in the making.”

A committee reviewed and narrowed the entries — 23 in all were submitted in the contest’s first year — and selected finalists for the inaugural awards. The two winners learned of their success at a ceremony in the Women’s Building Formal Lounge April 9. They received $250, a framed certificate and the opportunity to have their work published through the Center for the Humanities.

Upon McLeod’s death, Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton remembered the man as one of WUSTL’s “greatest citizens and leaders.” McLeod first joined the university in 1974 as an assistant professor of German and held several administrative positions throughout the years.

Provost Edward S. Macias, PhD, and several others made remarks at the writing prize ceremony.

The long-term goal of the writing prize is to encourage students to begin conducting research early in their undergraduate careers. It likewise will help faculty identify and nurture incoming students who show the potential to become strong researchers in the humanities and social sciences.

“It’s so exciting. Dean McLeod would be proud,” Mustakeem said. “Here’s an opportunity to say to students, ‘You matter. And look how you’re contributing to intellectual knowledge.’”

‘Be a sponge’ and other advice to help students succeed at summer internships

As students begin to leave campus for the summer, many will head off to internships, hoping to add to their classroom experiences and enhance their future opportunities by immersing themselves in the real world of work.

It’s a great way to spend the summer, said Mark Smith, Washington University in St. Louis’ associate vice chancellor for students and director of the Career Center, but to get the most out of the experience, it’s imperative that students have a clear plan.

Essentially, Smith said, it comes down to these questions: What do you want to know about yourself, the industry in which you are working, and the function you are performing? And what can you can learn by the end of the summer and incorporate into your career planning and course choices when you return?

Smith offers four tips that will help make a summer internship more meaningful and productive.

1. It’s essential to communicate upfront to your supervisors what kinds of experiences you want to have before the end of the internship.

“Don't assume that the people you are working with will automatically know what you want,” Smith said. “You need to communicate the learning experiences and exposure you'd like to get in this very short time frame. Don't let past interns determine your summer. Your needs and goals are unique to you. Be professional, be clear, and don't give up. Most everyone at your firm is inclined to want to see you have a positive experience. Let them know what that experience looks like from your perspective.”

2. Find informal ways to meet others within the organization.

“Grab some coffee with folks you don't work directly with,” Smith said. “Set up lunches every week with people who are interesting to you, outside of your area. People love to talk about their work and careers — their achievements, their challenges, where they want to go next, and what they would recommend to you. By doing these things you will stand out, build a network of associates, and most importantly, learn what you need to know about where you want to direct your career passions when you return to school.”

3. Set high expectations and make the most of the experience, especially in the first four weeks.

“Be a sponge,” Smith said. “Do more than expected. Contribute in ways outside of the scope of the role they gave you. It will open opportunities that they, and you, hadn't considered at the beginning of your program. If you don't do this at the start, and you wait for the internship to evolve, you won't optimize your learning experience.”

4. Keep a journal and ask yourself questions such as:

• Do I really like working for this size of an organization?

• Is this type of organization the best way to start off my career?

• Would I want to spend eight hours a day working with people who do this kind of work?

• Would I be happy starting my career in a rigid culture that pays well, but which doesn't offer me the personal independence I am used to?

• Is it critical to get a graduate degree to be promoted in this industry?

• Where do those around me get their personal and professional satisfaction?

• How do professionals in this organization keep up with all the new developments?

• How do you get promoted in this industry?

• Which are the best organizations in this industry? Why are they the best?

Smith emphasizes that upfront planning and hard work are the keys to a successful internship.

“Every summer thousands of interns realize, too late, what they could have experienced, if they only communicated at the beginning what they wanted, and given 110 percent from Day One,” he said.

Wǒmen (我们): Contemporary Chinese Art on display

Hung Liu, Bonsai, 1992. Photolithograph from two plates on Rives BFK paper, 22 1/2 x 30". Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. Gift of Island Press (formerly the Washington University School of Art Collaborative Print Workshop), 1993.

And just as this period has witnessed the emergence of China as a major international power, so too has it seen the arrival of contemporary Chinese art on the global stage.

Such is the backdrop for Wǒmen (我们): Contemporary Chinese Art, now on view at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum.

Curated by a trio of undergraduate students — Samantha Allen, Elizabeth Korb and Danielle Wu — the exhibition collects more than a dozen works by contemporary Chinese women artists, all created during this ongoing period of modernization and variously reflecting its hopes, illusions and realities.

The curators note that, though several artists engage with issues relating to gender politics, they generally resist the application of artistic labels, seeing themselves less as feminist artists than as individual practitioners who happen to be women.This approach is encapsulated in the exhibition title: The Chinese character “wǒmen” (我们) can be read as “women” in English, but it literally translates more broadly to “us” in Chinese.

And indeed, the works on view span a wide variety of thematic territory, shedding light on issues that affect not only individuals but also the Chinese population as a whole. Topics range from the effects of rapid urbanization and the role of Chinese identity in a globalized society to the impact of sociocultural reforms on the fabric of everyday life.

Wǒmen (我们): Contemporary Chinese Art represents the inaugural exhibition of the Arthur Greenberg Curatorial Fellowship, a competitive program jointly sponsored by the Kemper Art Museum, the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts and the Department of Art History & Archaeology in Arts & Sciences. It remains on view through May 26 in the museum’s Teaching Gallery.

The Kemper Art Museum is located near the intersection of Skinker and Forsyth boulevards. Regular hours are 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays; 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Fridays; and 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. The museum is closed Tuesdays.

For more information about the exhibition, call (314) 935-4523 or visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu.

Book idea gets boost from awards, faculty fellowship

Messbarger

Messbarger, professor of Italian in Arts & Sciences, said winning the two awards was “a complete surprise” and she is grateful for the validation the prizes give her book project.

The article, “The Re-Birth of Venus in Florence’s Royal Museum of Physics and Natural History,” appeared in the Journal of the History of Collections in 2012. It won the James L. Clifford Prize from the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies and the Percy G. Adams Prize, awarded by the Southeastern American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies.

Messbarger also is grateful for the resources afforded her as a faculty fellow. She will be freed from teaching and administrative duties and provided an office in the Center for the Humanities.

“As a faculty fellow, among the most important resources I will have is the time to research and write,” said Messbarger, who is also a professor of women, gender and sexuality studies, in Arts & Sciences. “Having the mental space to think has always marked the difference for me between a scholarly project that is competent and one that moves vivaciously in new directions.”

She also looks forward to collaborating with other faculty fellows.

“I will have a community, a precious thing to me,” she said. “I am not a scholar who relishes solitary study or alone time with my computer. I need colleagues with whom I can discuss my work and hear about theirs.

“This collaborative exchange among fellows and graduate students is a central part of the program and an aspect of my semester there about which I am particularly excited.”

Messbarger’s major research interests center on Italian Enlightenment culture, in particular the place and purpose of women in civic, academic and social life, and the intersection of art and science in the production of anatomical wax models during the age.

Her new book will focus on the real and symbolic links and ruptures between a wax, life-size Anatomical Venus created in Enlightenment-era Florence and the Venus de Medici of the Renaissance. The wax Venus was on display in the Royal Museum of Physics and Natural History, founded by Archduke of Tuscany Peter Leopold in 1775 “as a means to overthrow the regressive cultural authority of the Medici dynasty and launch a new era of Enlightenment.”

Messbarger was chosen to be a Center for the Humanities faculty fellow because her book project “is a fascinating and well-conceived project with wide-ranging appeal,” said Erin McGlothlin, PhD, interim director of the Center for the Humanities and associate professor of German in Arts & Sciences.

McGlothlin said the faculty fellows program provides research support for humanities scholars, who typically have fewer external opportunities for such support than their colleagues in nonhumanities fields.

“The goal of the program is to generate greater innovation in scholarship and teaching across disciplines in the humanities by providing fellowship for projects that involve interdisciplinary sharing and exchange,” she said.

McGlothlin can speak firsthand about the benefits of the fellowship. She was a member of the first class of Center for the Humanities faculty fellows in spring 2006.

“Not only did my faculty fellowship give me the time and resources critical for developing my research,” she said, “it also allowed me the opportunity to journey outside the confines of my home discipline and enter into a larger dialogue about the role of the humanities at Washington University in particular and in our contemporary culture more generally.”

To learn more about Messbarger’s research and previous publications, visit here.

Graduate students recognize faculty mentors

kevin lowder

The Graduate Student Senate at Washington University in St. Louis recognized eight faculty with Outstanding Faculty Mentor Awards during its 14th annual awards ceremony, held April 10 in the Women’s Building Formal Lounge. Five of the 2012-13 recipients are (from left) John M. Doris, PhD, professor of philosophy in Arts & Sciences; David Wang, PhD, associate professor of molecular microbiology and of pathology and immunology at the School of Medicine; David Balota, PhD, professor of psychology in Arts & Sciences; Wendy Auslander, PhD, the Barbara A. Bailey Professor of Social Work at the Brown School; and Lynne Tatlock, PhD, the Hortense and Tobias Lewin Distinguished Professor in the Humanities in Arts & Sciences. Not pictured are Gammon Earhart, PhD, associate professor of physical therapy; Nathan M. Jensen, PhD, associate professor of political science in Arts & Sciences; and Erik Trinkaus, PhD, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences. The awards are based on nominations by graduate students and designed to honor faculty members whose dedication to mentoring PhD students and commitment to excellence in graduate training have made a significant contribution to the quality of life and professional development of students in the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Special recognition for excellence in mentoring went to six other faculty members at the ceremony. To see the list of faculty award winners, visit here.

WUSTL Opera Workshop April 30 and May 2

The cover of the first installment to Charles Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood, published in 1870. More than a century later, Dickens' unfinished novel would inspire a Tony Award-winning musical, excerpts from which will be performed Tuesday and Thursday, April 30 and May 2.

Yes, he did, and a good one, too. In 1986, The Mystery of Edwin Drood by Rupert Holmes — perhaps known for chart-topping story-songs like “Escape” and “Him” — was nominated for 11 Tony Awards. It won five, including the “triple crown” of best musical, best book and best score.

Next week, the Washington University Opera Workshop will present excerpts from Drood and five other works as part of Spring Scene Studies, its semester-end performance.

The event is free and open to the public and will take place at 8 p.m. Tuesday and Thursday, April 30 and May 2, in the Ballroom Theater of the 560 Music Center.

The performance, which is presented in the round, will begin with excerpts from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1787) and Engelbert Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel (1893). The latter will feature additional singers from the WUSTL Chamber Chorus.

Next will be scenes from Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello (1887) and two songs from The Fantasticks (1960) by Harvey Schmidt and Tom Jones.

Concluding the program will be excerpts from Benjamin Britten’s Owen Wingrave (1970) and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which Holmes adapted from Charles Dickens’ final, uncompleted novel of the same title.

Musical direction is by senior lecturer Christine Armistead, with stage direction by lecturer Tim Ocel. Pianist will be Sandra Geary, teacher of applied music.

The performance is sponsored by the Department of Music in Arts & Sciences. The 560 Music Center is located in University City at 560 Trinity Ave.

For more information, call (314) 935-5566 or email daniels@wustl.edu.